The banking space is always full of activity, with RBI in particular being under the lens not just for the decision on interest rates but the financial environment as well. It is not surprising that the Banking Law Amendment Bill has raised interest once again for not being passed.

The Bill, when viewed along with the passage of changes in the Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002, reads well for the banking sector as it addresses the issues of both capital and asset quality (subsumed under prudential banking) in a limited manner. We all know that for sustaining growth of 8% per annum in the future, bank credit has to increase by over 20% per annum. This requires capital for banks, which will progressively pose a challenge given that we are moving over to Basel III, where the capital and liquidity requirements are more pressing. Therefore, having new banks makes a lot of sense as this will bring in the capital that is required. The next stop would be for RBI to work out the game-plan and set the ground rules. There are a number of corporate houses like Tata, L&T, Birla, etc, that are prepared to start such outfits or have their own NBFCs converted to a bank.

The second area where the Bill has focused on is the voting rights privilege. Increasing it to 10% for public sector banks (PSBs) and 26% in private banks is pragmatic as it provides more incentives to involve shareholders in the running of the bank, which improves transparency as well as governance and efficiency. This could be a useful step in moving further towards disinvestment of public sector banks as we get used to more private participation in the affairs of the bank. Third, RBI will have more powers to regulate acquisitions in this space. This does not really matter much as RBI is already quite powerful and we may not be seeing such activity concerning large banks. More likely, this would be for weaker or smaller banks, where there would not be any serious issue.

Fourth, the question of banks and ARCs being allowed to convert outstanding debt owed to them to equity or bidding for immoveable property that has been put for auction is useful for them as it means that they will address the critical part of NPAs. Banks should be pleased with this move as they are offered more options at a time when their NPAs have increased and they have been saddled with progressively increasing restructured assets. Discussions on these issues have, by and large, been more or less according to the script, which over months has managed to garner a reasonable level of acceptance. However, the issue that has become controversial pertains to allowing banks to enter the commodity futures market. This would have probably been one of the most revolutionary decisions taken by the government because given the pro-cyclical nature of growth of NPAs with agricultural production and industrial growth, there is a pressing need for a cover to be procured by banks. At present, agriculture has crop and weather insurance, which provides cover to the farmers, though not to the bank as recovery would still be its job.

As bank lending is predominantly against the existence of a commodity somewhere in the input-output matrix for a company or directly for farmers, there is a commodity price risk that is carried on its books. At the pre-harvest stage, the farmer carries a price and volumetric risk, of which the latter is covered by the insurance company. The bank lends to the farmer for inputs and the latter’s ability to repay the loan depends on the price at the time of harvest. Intuitively, it can be seen that the bank is better off in case the farmer hedges his price risk on a commodity exchange. However, today, farmers cannot access this market due to the absence of knowledge as well as their trading lot size, which is too small. A solution is for banks to act as aggregators for farmers as it pays them to hedge their risk in the eventuality of the crop failing. The banker only needs to convey the quantity of crop involved to the central treasury which puts in the order. This is what RBI had recommended in the draft report on warehouse receipt finance in 2005.

The same analogy can be carried for non-farm products, where often banks are impacted by volatility in prices of specific commodities like oilseeds, sugarcane, steel, aluminium, wheat, crude oil, etc. Here, banks can provide cover for themselves in case they take a corresponding position in the commodity derivative market with active trading in farm products on exchanges like NCDEX and energy products on MCX. Most of these products are offered on these exchanges or have proxy products that may be used. In fact, banks would be better off in case ‘options’ were permitted in this market as futures protects against downside risks while options lets one exit when conditions are better at the time of settlement of contract. But this needs the Forward Contract Regulation Act (FCRA) to be changed, which is another Bill pending in Parliament.

The FCRA Amendment Bill seeks to give autonomy to the Forward Markets Commission (FMC), which, in turn, would give it power to introduce new products which will include options and indices (intangibles). Therefore, for banks to be allowed into the commodity market, it would also be necessary to amend this Bill so that options are permitted as in the capital market. An interesting corollary here is that banks could also take proprietary trading positions in this segment, just like they do in the capital market. RBI would, however, have to set the regulatory processes to ensure that there is controlled trading that does not distort their own business models. This may still be a long way off.

The impasse in Parliament is ostensibly on account of futures trading by banks. Logically, the other elements that have been agreed upon should be passed immediately so that work can begin, especially on the issue of new banks being permitted, while the issue of futures trading can be separately debated. Or else we will have to wait again for a longer time period, which is not desirable for the banking system as we always seem to be returning to the starting line of a race that never seems to begin.

The Bill, when viewed along with the passage of changes in the Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002, reads well for the banking sector as it addresses the issues of both capital and asset quality (subsumed under prudential banking) in a limited manner. We all know that for sustaining growth of 8% per annum in the future, bank credit has to increase by over 20% per annum. This requires capital for banks, which will progressively pose a challenge given that we are moving over to Basel III, where the capital and liquidity requirements are more pressing. Therefore, having new banks makes a lot of sense as this will bring in the capital that is required. The next stop would be for RBI to work out the game-plan and set the ground rules. There are a number of corporate houses like Tata, L&T, Birla, etc, that are prepared to start such outfits or have their own NBFCs converted to a bank.

The second area where the Bill has focused on is the voting rights privilege. Increasing it to 10% for public sector banks (PSBs) and 26% in private banks is pragmatic as it provides more incentives to involve shareholders in the running of the bank, which improves transparency as well as governance and efficiency. This could be a useful step in moving further towards disinvestment of public sector banks as we get used to more private participation in the affairs of the bank. Third, RBI will have more powers to regulate acquisitions in this space. This does not really matter much as RBI is already quite powerful and we may not be seeing such activity concerning large banks. More likely, this would be for weaker or smaller banks, where there would not be any serious issue.

Fourth, the question of banks and ARCs being allowed to convert outstanding debt owed to them to equity or bidding for immoveable property that has been put for auction is useful for them as it means that they will address the critical part of NPAs. Banks should be pleased with this move as they are offered more options at a time when their NPAs have increased and they have been saddled with progressively increasing restructured assets. Discussions on these issues have, by and large, been more or less according to the script, which over months has managed to garner a reasonable level of acceptance. However, the issue that has become controversial pertains to allowing banks to enter the commodity futures market. This would have probably been one of the most revolutionary decisions taken by the government because given the pro-cyclical nature of growth of NPAs with agricultural production and industrial growth, there is a pressing need for a cover to be procured by banks. At present, agriculture has crop and weather insurance, which provides cover to the farmers, though not to the bank as recovery would still be its job.

As bank lending is predominantly against the existence of a commodity somewhere in the input-output matrix for a company or directly for farmers, there is a commodity price risk that is carried on its books. At the pre-harvest stage, the farmer carries a price and volumetric risk, of which the latter is covered by the insurance company. The bank lends to the farmer for inputs and the latter’s ability to repay the loan depends on the price at the time of harvest. Intuitively, it can be seen that the bank is better off in case the farmer hedges his price risk on a commodity exchange. However, today, farmers cannot access this market due to the absence of knowledge as well as their trading lot size, which is too small. A solution is for banks to act as aggregators for farmers as it pays them to hedge their risk in the eventuality of the crop failing. The banker only needs to convey the quantity of crop involved to the central treasury which puts in the order. This is what RBI had recommended in the draft report on warehouse receipt finance in 2005.

The same analogy can be carried for non-farm products, where often banks are impacted by volatility in prices of specific commodities like oilseeds, sugarcane, steel, aluminium, wheat, crude oil, etc. Here, banks can provide cover for themselves in case they take a corresponding position in the commodity derivative market with active trading in farm products on exchanges like NCDEX and energy products on MCX. Most of these products are offered on these exchanges or have proxy products that may be used. In fact, banks would be better off in case ‘options’ were permitted in this market as futures protects against downside risks while options lets one exit when conditions are better at the time of settlement of contract. But this needs the Forward Contract Regulation Act (FCRA) to be changed, which is another Bill pending in Parliament.

The FCRA Amendment Bill seeks to give autonomy to the Forward Markets Commission (FMC), which, in turn, would give it power to introduce new products which will include options and indices (intangibles). Therefore, for banks to be allowed into the commodity market, it would also be necessary to amend this Bill so that options are permitted as in the capital market. An interesting corollary here is that banks could also take proprietary trading positions in this segment, just like they do in the capital market. RBI would, however, have to set the regulatory processes to ensure that there is controlled trading that does not distort their own business models. This may still be a long way off.

The impasse in Parliament is ostensibly on account of futures trading by banks. Logically, the other elements that have been agreed upon should be passed immediately so that work can begin, especially on the issue of new banks being permitted, while the issue of futures trading can be separately debated. Or else we will have to wait again for a longer time period, which is not desirable for the banking system as we always seem to be returning to the starting line of a race that never seems to begin.

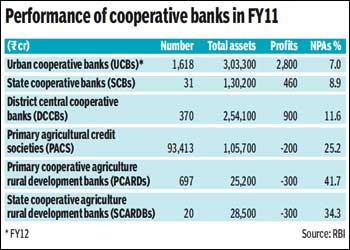

Within commercial banks, a little less than half of the non-performing assets (NPAs) originate in the priority sector (whose share in total credit is around 31-33%), and given that this sector is held sacrosanct, seldom do bankers raise objections and instead defend the concept as being necessary. In FY12, 4.4% of outstanding priority sector advances were classified as non-performing, while the same for non-priority sector was 2.4%. Further, growth in these NPAs was much higher than that in loans to this sector. Clearly, there are problems associated with such finance.

Within commercial banks, a little less than half of the non-performing assets (NPAs) originate in the priority sector (whose share in total credit is around 31-33%), and given that this sector is held sacrosanct, seldom do bankers raise objections and instead defend the concept as being necessary. In FY12, 4.4% of outstanding priority sector advances were classified as non-performing, while the same for non-priority sector was 2.4%. Further, growth in these NPAs was much higher than that in loans to this sector. Clearly, there are problems associated with such finance.

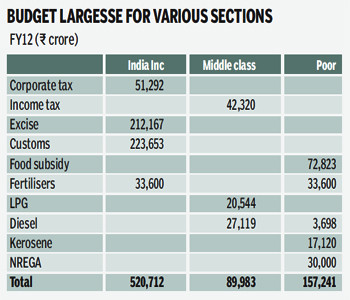

A question that is now being asked is, who does the government work for? In simple terms, when we critically analyse the budget of the central government, how does one decide as to who should get what benefit? This is important because we have this unique situation where everyone is critical of what goes on in the budget. The usual target is ‘subsidy’ where we feel that the middle class benefits from LPG and the super-rich from diesel and, therefore, the concept is irrelevant. Further, the money that goes to the poor is full of leakages and hence should be better allocated. We are overly critical of the PDS and keep suggesting various ways to better the system. But, invariably, what we hear is the corporate view, which works on the assumptions that the government should work like a corporate entity and use economic judgement when making allocations. This rationale cannot be disputed if we treat the government this way. Governments, however, have to work on the basis of political and social compulsions and are good at spending and not earning because any revenue earning measure is subject to external conditions such as growth and incentives that have to be provided to all segments of society. Therefore, while we may pontificate on what is right or wrong, the government proceeds on its own to strike a balance. An interesting exercise that can be attempted is to see how the government manages the budget by giving various benefits and incentives to different sections of society. For convenience, we can assume that we have India Inc, the middle class (which also includes the rich households) and the poor. The exercise is not perfect as it is difficult to match numbers with various sections of society as there are overlaps. Further, it is accepted that the assumptions can be questioned as they may not really hold in absolute terms. But, nonetheless, we can see how these benefits flow to sections. The budget captures one important section called revenue foregone on account of all the tax concessions that are given. This is important as we normally focus on the expenditures and pass judgement. But by giving concessions on the tax front, benefits are being drawn by all. The government calls them ‘tax expenditures’. This approach has been criticised for not being accurate as it is based on certain assumptions that may not be right. This is admitted in the budget document as it assumes that certain patterns do not change when certain taxes change. Still, as we are talking of the year gone by, a large part must be true as in the past this number given is around right to the extent of 80%. The accompanying table broadly allocates various identifiable budget items under these broad headings. Some of the assumptions made here are: First, excise and customs concessions are for the corporate sector as they are the ones who demand the same. It is true that these do get reflected in some way through as lower prices for consumers, but it is difficult to allocate the same. It is only the counter intuitive statement that can be used here for devolving a part to the consumers on grounds that in case these duties were not reduced, then prices would have gone up further. Second, all income tax benefits go to the middle class. Third, food subsidy is only for the poor, though this may not be fully correct. Fourth, in the case of fuel subsidy based on Teri’s study for FY11, the subsidy has been broken up into what goes to LPG and kerosene, which are allocated to the middle class and poor respectively, while the amount for diesel has been further sub-divided for irrigation which goes to the poor, while the rest resides with the middle class. Fifth, fertiliser subsidy actually goes to the corporate sector and half has been put under that head rather than poor, though there can be an argument that if this was not there, it would have meant higher prices. The table shows that the largest benefits do flow to India Inc, which can be justified as this is the most productive sector that provides a boost to investment and growth. The private corporate sector accounts for 33% of gross capital formation and if the public sector is added, it would be 64%. Therefore, it is necessary to provide incentives here to ensure that the growth process keeps ticking.The poor do receive the second largest benefits directly through various programmes that are made available. This is a social necessity for the government and, as can be seen on the expenditure rather than the revenue side, this section does not pay taxes. The clue here is to enhance the delivery systems to ensure that these targeted segments receive the benefits and that there are few leakages. The middle class, comprising the household sector, contributes to 36% of capital formation, which is also significant. It also accounts for 70% of savings and is a major consumer of goods produced by India Inc. This segment is also the most vulnerable when it comes to inflation as it consumes all goods, unlike the poor who have access to only food items. Quite clearly this segment is also an important constituent of the economy whose needs have to be addressed.The government hence has to strike a balance across all segments, given their individual contribution to the economic development of the country. Therefore, the argument that a certain class does not merit an incentive or benefit is really not on, and fortunately, the government understands this.

A question that is now being asked is, who does the government work for? In simple terms, when we critically analyse the budget of the central government, how does one decide as to who should get what benefit? This is important because we have this unique situation where everyone is critical of what goes on in the budget. The usual target is ‘subsidy’ where we feel that the middle class benefits from LPG and the super-rich from diesel and, therefore, the concept is irrelevant. Further, the money that goes to the poor is full of leakages and hence should be better allocated. We are overly critical of the PDS and keep suggesting various ways to better the system. But, invariably, what we hear is the corporate view, which works on the assumptions that the government should work like a corporate entity and use economic judgement when making allocations. This rationale cannot be disputed if we treat the government this way. Governments, however, have to work on the basis of political and social compulsions and are good at spending and not earning because any revenue earning measure is subject to external conditions such as growth and incentives that have to be provided to all segments of society. Therefore, while we may pontificate on what is right or wrong, the government proceeds on its own to strike a balance. An interesting exercise that can be attempted is to see how the government manages the budget by giving various benefits and incentives to different sections of society. For convenience, we can assume that we have India Inc, the middle class (which also includes the rich households) and the poor. The exercise is not perfect as it is difficult to match numbers with various sections of society as there are overlaps. Further, it is accepted that the assumptions can be questioned as they may not really hold in absolute terms. But, nonetheless, we can see how these benefits flow to sections. The budget captures one important section called revenue foregone on account of all the tax concessions that are given. This is important as we normally focus on the expenditures and pass judgement. But by giving concessions on the tax front, benefits are being drawn by all. The government calls them ‘tax expenditures’. This approach has been criticised for not being accurate as it is based on certain assumptions that may not be right. This is admitted in the budget document as it assumes that certain patterns do not change when certain taxes change. Still, as we are talking of the year gone by, a large part must be true as in the past this number given is around right to the extent of 80%. The accompanying table broadly allocates various identifiable budget items under these broad headings. Some of the assumptions made here are: First, excise and customs concessions are for the corporate sector as they are the ones who demand the same. It is true that these do get reflected in some way through as lower prices for consumers, but it is difficult to allocate the same. It is only the counter intuitive statement that can be used here for devolving a part to the consumers on grounds that in case these duties were not reduced, then prices would have gone up further. Second, all income tax benefits go to the middle class. Third, food subsidy is only for the poor, though this may not be fully correct. Fourth, in the case of fuel subsidy based on Teri’s study for FY11, the subsidy has been broken up into what goes to LPG and kerosene, which are allocated to the middle class and poor respectively, while the amount for diesel has been further sub-divided for irrigation which goes to the poor, while the rest resides with the middle class. Fifth, fertiliser subsidy actually goes to the corporate sector and half has been put under that head rather than poor, though there can be an argument that if this was not there, it would have meant higher prices. The table shows that the largest benefits do flow to India Inc, which can be justified as this is the most productive sector that provides a boost to investment and growth. The private corporate sector accounts for 33% of gross capital formation and if the public sector is added, it would be 64%. Therefore, it is necessary to provide incentives here to ensure that the growth process keeps ticking.The poor do receive the second largest benefits directly through various programmes that are made available. This is a social necessity for the government and, as can be seen on the expenditure rather than the revenue side, this section does not pay taxes. The clue here is to enhance the delivery systems to ensure that these targeted segments receive the benefits and that there are few leakages. The middle class, comprising the household sector, contributes to 36% of capital formation, which is also significant. It also accounts for 70% of savings and is a major consumer of goods produced by India Inc. This segment is also the most vulnerable when it comes to inflation as it consumes all goods, unlike the poor who have access to only food items. Quite clearly this segment is also an important constituent of the economy whose needs have to be addressed.The government hence has to strike a balance across all segments, given their individual contribution to the economic development of the country. Therefore, the argument that a certain class does not merit an incentive or benefit is really not on, and fortunately, the government understands this.