Two decades of reforms is a long enough period to do some introspection, especially today when there is an air of despondency with all fingers pointing in the direction of their absence. In fact, it is agreed today that more reforms is the only way out. There is a sense of déjà vu as we talk about those good old days of reforms that started in the nineties. There is also a counterview that the Indian growth story is exaggerated and that we are capable of growing only at 6 per cent and not in double digits. This is where these two books on reforms come in handy with their thought-provoking views on the impact of reforms.

Uma Kapila’s Two Decades Of Economic Reform is a compilation of 20 articles by eminent economists who have either worked on the government’s side in bringing about these reforms or have followed them very closely as their critics. The consensus is that economic reforms have been a turning point and there is no looking back (Deepak Mohanty). D. Subbarao talks about making the elephant dance again as the growth story is intact and we only have to get our act together by adding another chapter. The solutions offered by the central banker are well known and quite to the point. Subir Gokarn shows how reforms helped bring in certain resilience during the financial crisis while Arvind Panagariya illustrates how all states have gained from reforms as the poverty ratio has come down, even though the absolute number of the poor is still high. There are other incisive articles such as the one by Anand Sinha on legislative reforms. Manmohan Singh and Pranab Mukherjee eloquently explain how reforms have delivered superior solutions. But, is that really so? Because if they have, then it is only a matter of time before we will be back on track.

Amid the set of articles praising the economic performance, N.A. Majumdar provides a refreshing view. His article titled ‘From Friedman to Gandhi’ makes us stop and think because, while we extol the virtues of reforms and the proliferation of consumerism, there is a shadow alongside which we tend to often overlook. He shows how the first phase of reforms until 2004 was retrogressive, when we were soaked in the market theology of the World Bank and the IMF, skipped the basic issues of development, that is agriculture, and had a disdain for anything that had to do with the poor. The subsequent phase is when we have gone back to Gandhi, when even the financial crisis exposed the errors of unbridled capitalism. Now we are addressing the concerns of the poor, which is logical and fair. In fact, he argues that this entire business of targeting the public distribution system has exacerbated poverty in India, and terms it a development atrocity. He extends this logic to our interest rate policy, saying it is biased against the farmer who pays 12 per cent while top corporates get away with 6 per cent. Majumdar is clearly at odds with Bibek Debroy who maintains that we should listen to our “brains” and not our “bleeding hearts” and move ahead.

The book also focuses on the farm sector and inclusive growth, with three stalwarts — Hanumantha Rao, V.S. Vyas and Ashok Gulati — writing on different aspects. Gulati argues that while we talk a lot about 4 per cent growth in agriculture, we have never made any attempt to create structures for the same, such as a 15 per cent rate of capital formation. He says we should be more pragmatic and bring in the essential linkages to make such goals more realistic. He suggests reforms in the system and points out how marketing practices as well as the Essential Commodities Act and the Agriculture Produce Marketing Committee need to change. These laws have long served their purpose and are now working against the interest of the sector by introducing rigidities. Vyas centres his discussion on the size of land holdings and the need to make agriculture more robust, while Rao asks us to be more patient as the road towards inclusive growth is slow and should be peaceful.

The rest of the articles are insightful but really do not go beyond the official view that reforms have taken us much ahead. The Five-year Plan perspective is well elucidated by Montek Singh Ahluwalia, while Vijay Kelkar provides his take on the disinvestment debate. There is a delightful piece by Kaushik Basu, who never disappoints as he distinguishes between harassment and non-harassment bribes and is sympathetic to those who have to give the former.

The other book on reforms, titled India’s Reforms: How They Produced Inclusive Growth by Arvind Panagariya and Jagdish Bhagwati, takes a different route to assess the impact of reforms. They are definitely pro-reforms economists who believe that this is the only way forward for the nation. They address two sets of issues through three articles by each. The first set includes reforms and democracy while the other is linked with trade, poverty and inequality.

They argue that reforms actually started in the seventies, got focus in the eighties and were well projected in a concerted manner in the nineties. Hence, to say that reforms were dictated by the IMF would not be fair, though the crisis could be called the tipping point. The authors use the case studies of progress in telecom and automobiles to show how prosperity has spread across the country.

They have dealth with the various issues using the Q&A approach: they take up issues raised by critics and make their point using facts. The focus here is on how electorates vote parties back to power because of the impact of growth and reforms. They have used the 2009 elections to show that the ruling coalition came back to power because of performance, which proves that not only did people benefit from the policies but also favoured the Congress in turn. This theory is supported by the view that in 2009, the incumbents in high-growth states won 85 per cent of the seats while it was just 52 per cent and 10 per cent in medium- and low-growth states. More importantly, there was no difference in the urban and rural areas. They also credit the NDA for the telecom revolution.

At another level, they show how the opening of the economy and foreign trade helped lower the incidence of poverty, though they agree that a lot more needs to be done. Their research showed that 1 per cent reduction in the tariff rate led to 0.57 per cent reduction in the poverty ratio.

Both these pro-reform books are extremely readable. Kapila’s collection is comprehensive, though there is a bias towards the establishment. Bhagwati and Panagariya, on the other hand, explore new hypotheses to show that reforms have actually delivered, which are extremely engaging, even if you do not agree with the approach, assumptions and conclusions.

Uma Kapila’s Two Decades Of Economic Reform is a compilation of 20 articles by eminent economists who have either worked on the government’s side in bringing about these reforms or have followed them very closely as their critics. The consensus is that economic reforms have been a turning point and there is no looking back (Deepak Mohanty). D. Subbarao talks about making the elephant dance again as the growth story is intact and we only have to get our act together by adding another chapter. The solutions offered by the central banker are well known and quite to the point. Subir Gokarn shows how reforms helped bring in certain resilience during the financial crisis while Arvind Panagariya illustrates how all states have gained from reforms as the poverty ratio has come down, even though the absolute number of the poor is still high. There are other incisive articles such as the one by Anand Sinha on legislative reforms. Manmohan Singh and Pranab Mukherjee eloquently explain how reforms have delivered superior solutions. But, is that really so? Because if they have, then it is only a matter of time before we will be back on track.

Amid the set of articles praising the economic performance, N.A. Majumdar provides a refreshing view. His article titled ‘From Friedman to Gandhi’ makes us stop and think because, while we extol the virtues of reforms and the proliferation of consumerism, there is a shadow alongside which we tend to often overlook. He shows how the first phase of reforms until 2004 was retrogressive, when we were soaked in the market theology of the World Bank and the IMF, skipped the basic issues of development, that is agriculture, and had a disdain for anything that had to do with the poor. The subsequent phase is when we have gone back to Gandhi, when even the financial crisis exposed the errors of unbridled capitalism. Now we are addressing the concerns of the poor, which is logical and fair. In fact, he argues that this entire business of targeting the public distribution system has exacerbated poverty in India, and terms it a development atrocity. He extends this logic to our interest rate policy, saying it is biased against the farmer who pays 12 per cent while top corporates get away with 6 per cent. Majumdar is clearly at odds with Bibek Debroy who maintains that we should listen to our “brains” and not our “bleeding hearts” and move ahead.

|

| India’s Reforms:How they Produced Inclusive Growth By Jagdish Bhagwati, Arvind Panagariya OUP Pages: 312 |

The rest of the articles are insightful but really do not go beyond the official view that reforms have taken us much ahead. The Five-year Plan perspective is well elucidated by Montek Singh Ahluwalia, while Vijay Kelkar provides his take on the disinvestment debate. There is a delightful piece by Kaushik Basu, who never disappoints as he distinguishes between harassment and non-harassment bribes and is sympathetic to those who have to give the former.

The other book on reforms, titled India’s Reforms: How They Produced Inclusive Growth by Arvind Panagariya and Jagdish Bhagwati, takes a different route to assess the impact of reforms. They are definitely pro-reforms economists who believe that this is the only way forward for the nation. They address two sets of issues through three articles by each. The first set includes reforms and democracy while the other is linked with trade, poverty and inequality.

They argue that reforms actually started in the seventies, got focus in the eighties and were well projected in a concerted manner in the nineties. Hence, to say that reforms were dictated by the IMF would not be fair, though the crisis could be called the tipping point. The authors use the case studies of progress in telecom and automobiles to show how prosperity has spread across the country.

They have dealth with the various issues using the Q&A approach: they take up issues raised by critics and make their point using facts. The focus here is on how electorates vote parties back to power because of the impact of growth and reforms. They have used the 2009 elections to show that the ruling coalition came back to power because of performance, which proves that not only did people benefit from the policies but also favoured the Congress in turn. This theory is supported by the view that in 2009, the incumbents in high-growth states won 85 per cent of the seats while it was just 52 per cent and 10 per cent in medium- and low-growth states. More importantly, there was no difference in the urban and rural areas. They also credit the NDA for the telecom revolution.

At another level, they show how the opening of the economy and foreign trade helped lower the incidence of poverty, though they agree that a lot more needs to be done. Their research showed that 1 per cent reduction in the tariff rate led to 0.57 per cent reduction in the poverty ratio.

Both these pro-reform books are extremely readable. Kapila’s collection is comprehensive, though there is a bias towards the establishment. Bhagwati and Panagariya, on the other hand, explore new hypotheses to show that reforms have actually delivered, which are extremely engaging, even if you do not agree with the approach, assumptions and conclusions.

Two Decades of Economic Reforms Edited by Uma Kapila Academic Foundation Pages: 392

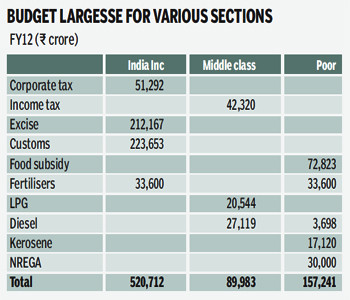

A question that is now being asked is, who does the government work for? In simple terms, when we critically analyse the budget of the central government, how does one decide as to who should get what benefit? This is important because we have this unique situation where everyone is critical of what goes on in the budget. The usual target is ‘subsidy’ where we feel that the middle class benefits from LPG and the super-rich from diesel and, therefore, the concept is irrelevant. Further, the money that goes to the poor is full of leakages and hence should be better allocated. We are overly critical of the PDS and keep suggesting various ways to better the system. But, invariably, what we hear is the corporate view, which works on the assumptions that the government should work like a corporate entity and use economic judgement when making allocations. This rationale cannot be disputed if we treat the government this way. Governments, however, have to work on the basis of political and social compulsions and are good at spending and not earning because any revenue earning measure is subject to external conditions such as growth and incentives that have to be provided to all segments of society. Therefore, while we may pontificate on what is right or wrong, the government proceeds on its own to strike a balance. An interesting exercise that can be attempted is to see how the government manages the budget by giving various benefits and incentives to different sections of society. For convenience, we can assume that we have India Inc, the middle class (which also includes the rich households) and the poor. The exercise is not perfect as it is difficult to match numbers with various sections of society as there are overlaps. Further, it is accepted that the assumptions can be questioned as they may not really hold in absolute terms. But, nonetheless, we can see how these benefits flow to sections. The budget captures one important section called revenue foregone on account of all the tax concessions that are given. This is important as we normally focus on the expenditures and pass judgement. But by giving concessions on the tax front, benefits are being drawn by all. The government calls them ‘tax expenditures’. This approach has been criticised for not being accurate as it is based on certain assumptions that may not be right. This is admitted in the budget document as it assumes that certain patterns do not change when certain taxes change. Still, as we are talking of the year gone by, a large part must be true as in the past this number given is around right to the extent of 80%. The accompanying table broadly allocates various identifiable budget items under these broad headings. Some of the assumptions made here are: First, excise and customs concessions are for the corporate sector as they are the ones who demand the same. It is true that these do get reflected in some way through as lower prices for consumers, but it is difficult to allocate the same. It is only the counter intuitive statement that can be used here for devolving a part to the consumers on grounds that in case these duties were not reduced, then prices would have gone up further. Second, all income tax benefits go to the middle class. Third, food subsidy is only for the poor, though this may not be fully correct. Fourth, in the case of fuel subsidy based on Teri’s study for FY11, the subsidy has been broken up into what goes to LPG and kerosene, which are allocated to the middle class and poor respectively, while the amount for diesel has been further sub-divided for irrigation which goes to the poor, while the rest resides with the middle class. Fifth, fertiliser subsidy actually goes to the corporate sector and half has been put under that head rather than poor, though there can be an argument that if this was not there, it would have meant higher prices. The table shows that the largest benefits do flow to India Inc, which can be justified as this is the most productive sector that provides a boost to investment and growth. The private corporate sector accounts for 33% of gross capital formation and if the public sector is added, it would be 64%. Therefore, it is necessary to provide incentives here to ensure that the growth process keeps ticking.The poor do receive the second largest benefits directly through various programmes that are made available. This is a social necessity for the government and, as can be seen on the expenditure rather than the revenue side, this section does not pay taxes. The clue here is to enhance the delivery systems to ensure that these targeted segments receive the benefits and that there are few leakages. The middle class, comprising the household sector, contributes to 36% of capital formation, which is also significant. It also accounts for 70% of savings and is a major consumer of goods produced by India Inc. This segment is also the most vulnerable when it comes to inflation as it consumes all goods, unlike the poor who have access to only food items. Quite clearly this segment is also an important constituent of the economy whose needs have to be addressed.The government hence has to strike a balance across all segments, given their individual contribution to the economic development of the country. Therefore, the argument that a certain class does not merit an incentive or benefit is really not on, and fortunately, the government understands this.

A question that is now being asked is, who does the government work for? In simple terms, when we critically analyse the budget of the central government, how does one decide as to who should get what benefit? This is important because we have this unique situation where everyone is critical of what goes on in the budget. The usual target is ‘subsidy’ where we feel that the middle class benefits from LPG and the super-rich from diesel and, therefore, the concept is irrelevant. Further, the money that goes to the poor is full of leakages and hence should be better allocated. We are overly critical of the PDS and keep suggesting various ways to better the system. But, invariably, what we hear is the corporate view, which works on the assumptions that the government should work like a corporate entity and use economic judgement when making allocations. This rationale cannot be disputed if we treat the government this way. Governments, however, have to work on the basis of political and social compulsions and are good at spending and not earning because any revenue earning measure is subject to external conditions such as growth and incentives that have to be provided to all segments of society. Therefore, while we may pontificate on what is right or wrong, the government proceeds on its own to strike a balance. An interesting exercise that can be attempted is to see how the government manages the budget by giving various benefits and incentives to different sections of society. For convenience, we can assume that we have India Inc, the middle class (which also includes the rich households) and the poor. The exercise is not perfect as it is difficult to match numbers with various sections of society as there are overlaps. Further, it is accepted that the assumptions can be questioned as they may not really hold in absolute terms. But, nonetheless, we can see how these benefits flow to sections. The budget captures one important section called revenue foregone on account of all the tax concessions that are given. This is important as we normally focus on the expenditures and pass judgement. But by giving concessions on the tax front, benefits are being drawn by all. The government calls them ‘tax expenditures’. This approach has been criticised for not being accurate as it is based on certain assumptions that may not be right. This is admitted in the budget document as it assumes that certain patterns do not change when certain taxes change. Still, as we are talking of the year gone by, a large part must be true as in the past this number given is around right to the extent of 80%. The accompanying table broadly allocates various identifiable budget items under these broad headings. Some of the assumptions made here are: First, excise and customs concessions are for the corporate sector as they are the ones who demand the same. It is true that these do get reflected in some way through as lower prices for consumers, but it is difficult to allocate the same. It is only the counter intuitive statement that can be used here for devolving a part to the consumers on grounds that in case these duties were not reduced, then prices would have gone up further. Second, all income tax benefits go to the middle class. Third, food subsidy is only for the poor, though this may not be fully correct. Fourth, in the case of fuel subsidy based on Teri’s study for FY11, the subsidy has been broken up into what goes to LPG and kerosene, which are allocated to the middle class and poor respectively, while the amount for diesel has been further sub-divided for irrigation which goes to the poor, while the rest resides with the middle class. Fifth, fertiliser subsidy actually goes to the corporate sector and half has been put under that head rather than poor, though there can be an argument that if this was not there, it would have meant higher prices. The table shows that the largest benefits do flow to India Inc, which can be justified as this is the most productive sector that provides a boost to investment and growth. The private corporate sector accounts for 33% of gross capital formation and if the public sector is added, it would be 64%. Therefore, it is necessary to provide incentives here to ensure that the growth process keeps ticking.The poor do receive the second largest benefits directly through various programmes that are made available. This is a social necessity for the government and, as can be seen on the expenditure rather than the revenue side, this section does not pay taxes. The clue here is to enhance the delivery systems to ensure that these targeted segments receive the benefits and that there are few leakages. The middle class, comprising the household sector, contributes to 36% of capital formation, which is also significant. It also accounts for 70% of savings and is a major consumer of goods produced by India Inc. This segment is also the most vulnerable when it comes to inflation as it consumes all goods, unlike the poor who have access to only food items. Quite clearly this segment is also an important constituent of the economy whose needs have to be addressed.The government hence has to strike a balance across all segments, given their individual contribution to the economic development of the country. Therefore, the argument that a certain class does not merit an incentive or benefit is really not on, and fortunately, the government understands this.