There were elections held in four states and a Union Territory while in Uttar Pradesh, panchayat polls were held in the same period. At that point, none of the parties cared much about safety and rallies were held, as they would have been in pre-Covid years. However, once the results were out, there was a battle cry for lockdowns. Such schizophrenic behaviour is not unusual in India

When the assembly elections were held in April it did appear quite ludicrous, as rallies led to people flouting social distancing norms. There were elections in four states and a Union Territory while in Uttar Pradesh, panchayat polls were held in the same period. At that point, none of the political parties cared much about safety and rallies were held, as would have been the case in pre-Covid years. However, once the results were out and the new governments were in place, there was a battle cry for lockdowns and people were not allowed to move out. Such schizophrenic behaviour is not unusual in India.

This was also the time when the Kumbh Mela was in progress in Uttarakhand. When the rallies were on, politicians argued that the virus would not spread because of such gatherings, as Maharashtra and Karnataka were two states which had the highest caseloads, despite not having held any election rallies. As over nine weeks have passed since the results were announced, it would be interesting to see how the caseload has moved over time.

Timeline of cases

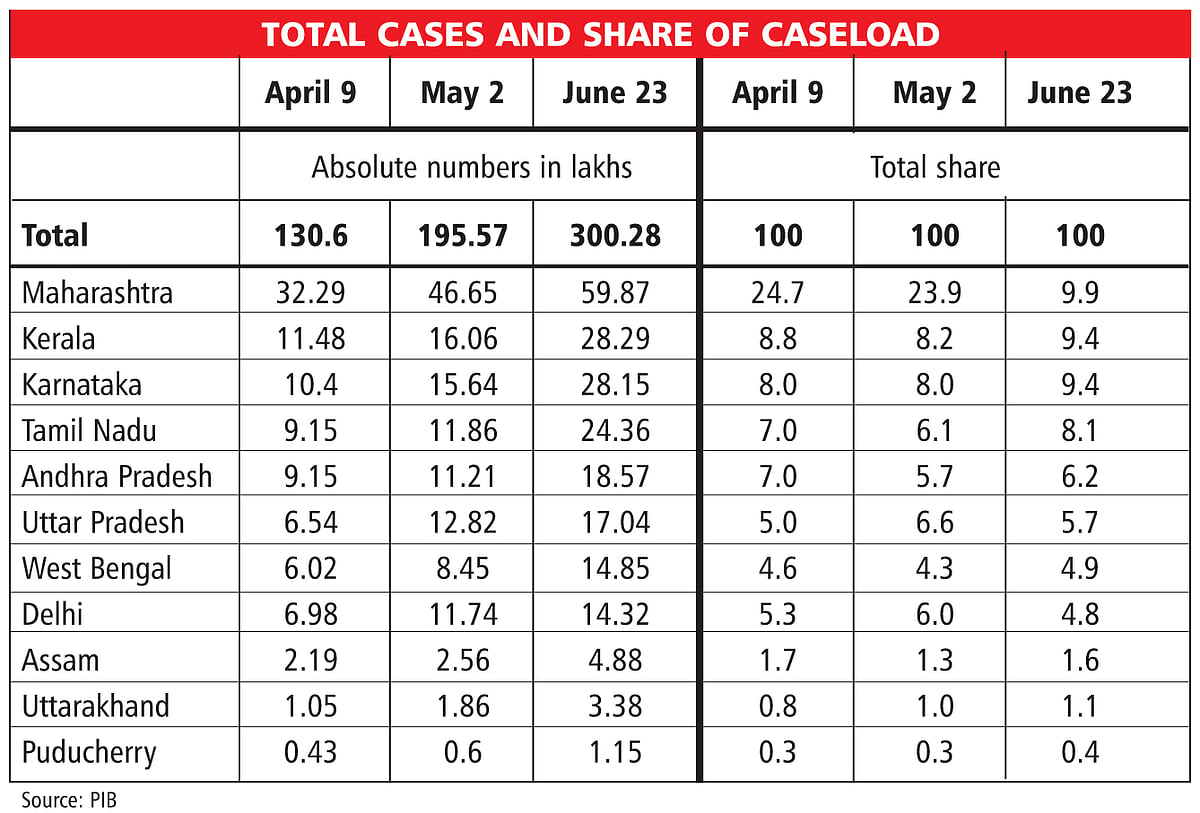

Three points of time have been chosen – April 9, May 2 and June 23. Some interesting facts follow from the data on aggregate caseloads. Maharashtra has the highest caseload, accounting for nearly 25 per cent of the total of 130 lakh cases in April. By June, the total number of cases increased to 300 lakh but Maharashtra’s share came down to 20 per cent.

The same was seen for Uttarakhand too, with the number of infections increasing and the share going up at a gentle pace. Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh had also witnessed an increased share as the second wave was quite widespread. But Gujarat, MP and Bihar witnessed a decline in share in the post-May period.

The exception was Maharashtra, where the share came down in both the periods. But then it could be argued that the virus originated in this state and then spread to the others and hence the damage was done in April itself. In the case of Uttar Pradesh and Delhi, April was an unfavourable month, but post-May, there was a decline in their respective shares. In fact, post-May 2, the three southern states had a share of almost 12 per cent each in incremental infections, just lower than that of Maharashtra, which was at 12.6 per cent.

Infections up in poll-bound states

Hence, infections increased in election states, though some non-election states also witnessed such setbacks. If growth rates are reckoned over May 2, then poll-bound states and Union Territory fare badly, with Tamil Nadu, Puducherry and Assam, all having above 90 per cent increase. Uttarakhand, West Bengal and Kerala witnessed growth of 75-80 per cent while it was less than 30 per cent for Delhi and Maharashtra and slightly higher than 30 per cent for UP.

The other interesting thing about state performance can be gauged by the death rate. This is quite disturbing, as the average for the country is 1.3 per cent, but states like Maharashtra and Uttarakhand have a ratio of 2.1 per cent. The highest is logged by Punjab with 2.7 per cent, even though the total number of cases was relatively lower, at 5.93 lakhs. This reflects both the severity of the disease as well as the state health structures.

Robust health systems

In this context, Kerala has done extremely well, as with the second highest caseload, the death rate was just 0.4 per cent, which redounds to the credit of the health system. The states of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Rajasthan and Odisha have all registered death rates of less than 1 per cent. Once again, Andhra Pradesh had a high caseload but managed to control deaths, which is creditable. Tamil Nadu, West Bengal and Karnataka have a death rate of 1.2-1.3 per cent while that for Delhi is high, at 1.7 per cent.

To conclude, it could be said that the elections did cause an increase in caseloads even while some non-elections states also witnessed an increase. Some states, especially in the south, have robust health systems, which helped mitigate the impact of the pandemic as revealed by the lower death rates.

No comments:

Post a Comment