The Economic Survey is a review of everything that has happened so far, with a prognosis on what to expect in the coming year. In terms of numbers, most of the data presented for the running year is already known, which includes the NSO data on gross domestic product (GDP), index of industrial production (IIP), and trade and so on. The point of interest really is in the outlook, and here the Economic Survey is positive about the ‘India story’.

GDP growth for the year is projected at 6-6.8 per cent with a baseline of 6.5 per cent, which is in accordance with Bank of Baroda’s forecast of 6 – 6.5 per cent. This is good news, as a number of researchers have spoken of numbers as low as 5 – 5.5 per cent. The Survey points to the strong domestic economy, which will provide immunity to an extent from the global recession. This is sound reasoning and the number also tallies well with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which has retained its forecast at 6.1 per cent for the year.

The other point of interest is the nominal GDP growth rate that has been placed at 11 per cent. This number may not necessarily be the starting point for the budget, which is to be announced on Wednesday, but gives a clue that the growth assumption will be close. It is important because the entire edifice of the budget is built on this number as it will determine the level of fiscal deficit that can be tolerated as we move along the path of fiscal prudence. In all likelihood, a double-digit number will allow room as the nominal number will be close to Rs 300 trillion, on which even a fiscal deficit ratio of 6 per cent will justify a deficit of Rs 18 trillion.

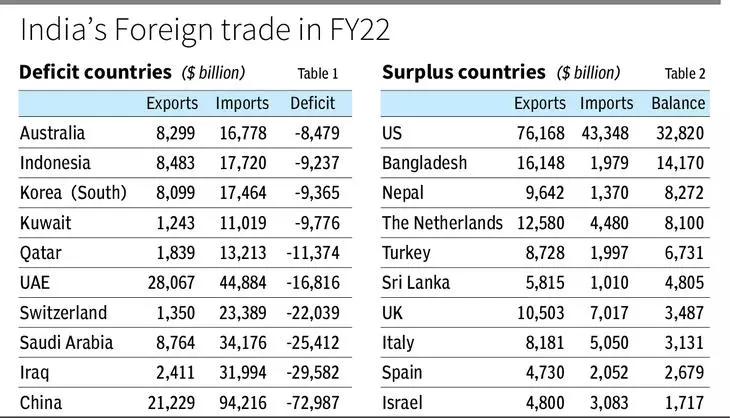

The Survey points out that a higher GDP growth number in an environment of shadows in the West will also mean that both consumption and investment will be up, thus increasing imports that will add to the current account deficit (CAD) and hence pressurise the currency.

The first part needs to play out, because in fiscal 2022-23 (FY23) we have seen consumption rising mainly due to the pent up demand phenomenon, which coupled with inflation helped to garner higher revenue. While investment had improved, it was sector specific with the infra based industries witnessing higher investment compared with the consumer based industries. This matrix does not look too strong and hence there can be some skepticism on whether it can be sustained.

Interestingly, the Survey does not believe that high inflation will come in the way of consumption, which has to be monitored because there are already signs of weakening demand. In FY23, people spent money at the cost of savings. But now with the pent up demand being exhausted, households are preferring to save than spend. Further, the Survey is also positive on corporate balance sheets, which in FY23, have tended to be skewed. Profits of companies have been under pressure due to elevated input costs that have tended to come in the way of profit growth.

On inflation the Survey is still cautious. This also means that it has signaled that elevated interest rates may be there for some more time. This rhymes with the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI’s) view that even when inflation comes down, one has to be watchful on repo rate changes as the climate is uncertain. With China likely to recover, it means that there could be commodity price pressures once again.

On the whole, the Survey is assuring, and though it believes that we have regained lost ground completely, we may have to do some close monitoring for another six months before celebrating.